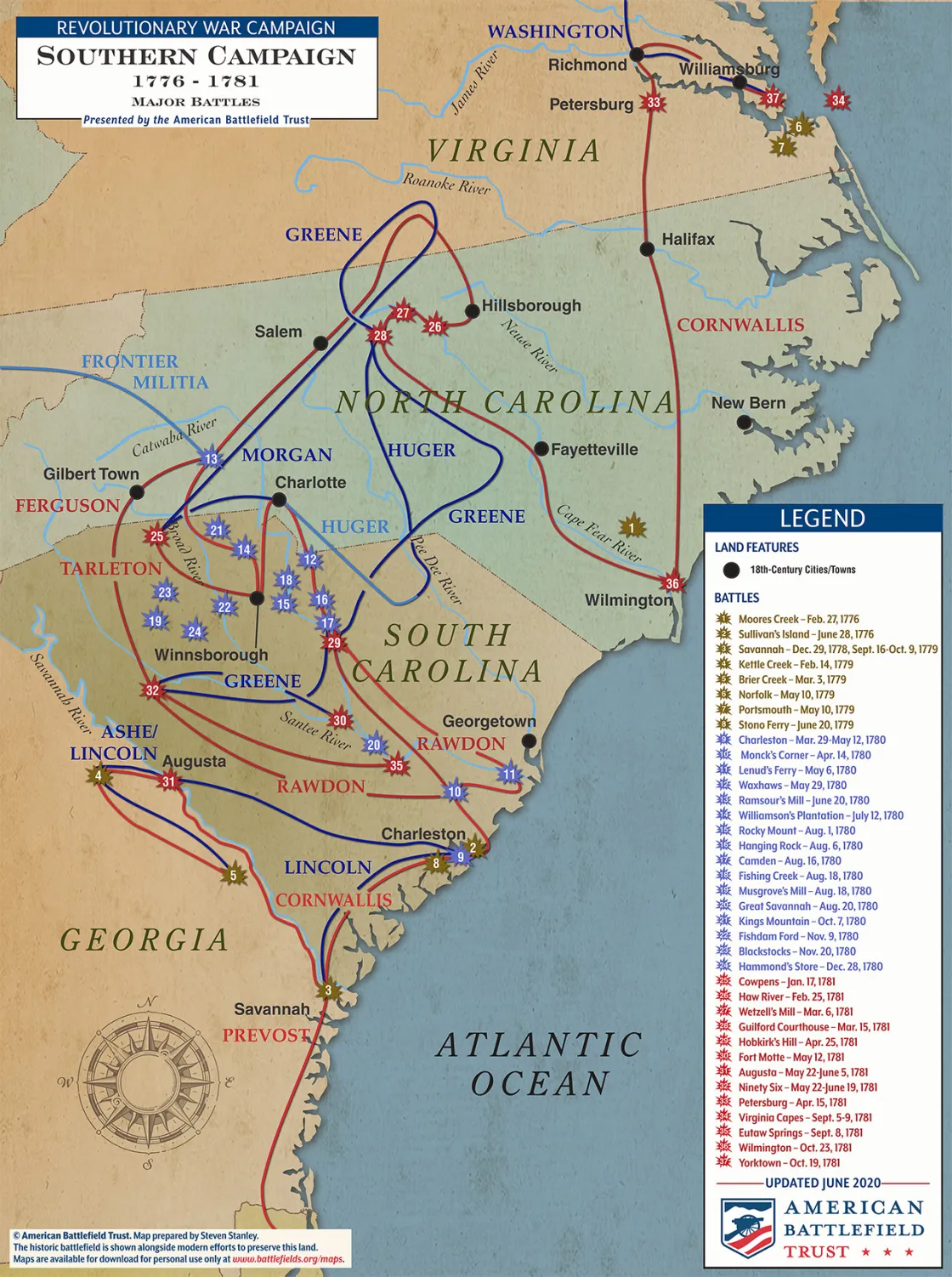

The Southern Campaign | 1776 - 1781

Reposted from battlefields.org

In the wake of the Saratoga Campaign, the British high command in London began to reassess how they prosecuted the war in North America. To many members of the Cabinet, New England was the problem child that they could not discipline. It seemed as if this entire rebellion manifested itself in New England—from the Boston Tea Party to the Boston Massacre and the Battles of Lexington & Concord—New England was the hotbed of hotheads. Militarily, Crown forces attempted to suppress and then cut off the northern from their sister colonies, thus far, to no avail. A new strategy was needed if the British Empire in North America was to remain mostly intact.

Enter Charles Jenkinson, an undersecretary in the Treasury. Jenkinson suggested that the war effort be shifted from New England to the south. Why did he propose this new “Southern Strategy?” Simply put, economics. The New England colonies produced many of the same products and goods as the British Isles, but the Southern colonies were a different story. Rice, indigo, tobacco, and other cash crops abounded. Crops that could not be produced in other parts of the Empire. The institution of chattel slavery helped to keep the wholesale prices of these products low, and British mercantilism could profit from cornering the market and selling the goods for substantial profits. The undersecretary and others in London also felt that the Southern people supported Toryism, and by default were more apt to take up arms as Loyalists. These Loyalist forces could be relied upon to bolster the British war effort lending manpower to an army that had been at war with their own colonists since 1775, while having to maintain a vast empire abroad. If the Crown forces could subdue the South, and isolate it from their sister colonies, the Empire would have a powerful bargaining chip when it came to peace negotiations. From a coldly economic standpoint, if the New England colonies became independent, that was not as great of a loss to Britain financially as the loss of their Southern colonies.

As usual, the powers that be in London were out of touch with the war on the ground in North America. Apparently, they forgot about the Mecklenburg (NC) Declaration of Independence (1775), the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), and the Battles at Moore’s Creek Bridge, Great Bridge, and Charleston (Sullivan’s Island) earlier in the war. While they may not have been as vocal as their Northern brethren, the Southern colonies were just as prepared to fight for their independence.

In late 1778, the British renewed their dormant efforts to subjugate their Southern colonies by launching a foray into Georgia. As the southernmost rebellious colony, Georgia bordered Florida, which came into British hands at the end of the Seven Years War and was divided by the British into East and West Florida. It was believed that the Georgians would welcome Crown assistance and protection from Native Americans. On December 29, 1778, the city of Savannah fell to a Torie expedition. As George Washington held the principal British army at bay in New York and nurtured the new Franco-American alliance, the battle for the fate of the British North American colonies now rested on the shoulders of Patriots in the South. And these Patriots were more than up to the task of throwing off the yolk of King George III.