10 Facts: The Battle of Camden

Reposted from battlefields.org

Here are 10 facts about the British victory at the Battle of Camden amidst the struggle for control of the Carolinas during the American Revolution.

Fact #1: Although they forced the surrender of the American Southern Army at Charleston, the British Army had a very difficult time controlling South Carolina.

On May 12, 1780, the American Southern Army surrendered at Charleston, South Carolina. Nearly 6,000 Americans were now out of the war and there was no organized army left in the south. British strategy to focus their efforts on the south was proving fruitful. At that point, the cities of Savannah and Charleston were under British control. Leaving Lord Cornwallis in command in the south, Sir Henry Clinton sailed back to New York. Cornwallis was to reestablish the Royal government in South Carolina and move north to take control of North Carolina. Quickly, however, Cornwallis realized that although his army could win battles, they could not control the Carolinas. While few Loyalists rallied around the King’s standard, Patriot militia and guerilla forces were effective in hitting British outposts. Soon, civil war broke out across the Carolinas and Cornwallis realized that reestablishing British authority was harder than winning a stand-up battle.

Fact #2: General Horatio Gates was not George Washington’s choice to lead the new southern army.

With the surrender of the Continental Army under Major General Benjamin Lincoln in Charleston, SC on May 12, 1780, the Americans lost 4,000 men underarms. George Washington, who had already sent Continental forces under Major General Johann de Kalb to assist Charleston, wanted to send his trusted subordinate, Nathaniel Greene, to reconstitute a new southern army with de Kalb’s men as a nucleus. Unfortunately, the politics of the Continental Congress led to the appointment of Horatio Gates. Divisions in the Continental Congress led to Washington and Gates factions, with many believing Gates’ victory at Saratoga gave him the right to replace Washington. When Charleston fell, Gates lobbied hard to lead the new southern army without having to report to Washington. Washington, always attentive to civilian control of the military, differed with Congress’ decision to give Gates the command in the south.

Fact #3: The summer of 1780 in South Carolina was a civil war.

After the surrender of Charleston in May 1780, British General Lord Cornwallis sought to institute the colonial civil government. The thought was, with the surrender of Charleston and the Southern American Army, Georgia, South Carolina, and soon North Carolina would all fall back in line under Royal rule. Cornwallis sought to establish outposts across South Carolina, where British military forces could enforce the rule of law, defend the Loyalist population, and defend against any Continental force coming from the north. It became obvious that the British overestimated the amount of Loyalists in South Carolina. Only hundreds, not thousands, of Loyalists pledged their loyalty to the Crown and took up arms. Meanwhile, American partisans such as Thomas Sumter, Francis Marion, and Andrew Pickens raided the British outposts, supply lines, and Loyalist farms with impunity. Loyalist units under Banastre Tarleton, John Carden, Christian Huck, and others did their best to fight the Patriot militias, but they could not keep control of the state. A majority of the brutal fighting that occurred that summer across South Carolina were between American Patriot forces and Loyalists, not British regulars. Neighbors, friends, families, and communities were all torn apart by civil war.

Fact #4: General Horatio Gates overestimated the strength of his “Grand Army.”

When General Horatio Gates arrived in North Carolina to take command of the reconstituted American Southern Army, he dubbed it the “Grand Army.” Gates could only count just over a thousand Continental soldiers from Maryland and Delaware in his army. Gates expected reinforcements from the militia units of Virginia and North Carolina to join him, as well as partisan units under Marion and Sumter. On August 13th, as Gates made his plans to march south from Rugeley's Mill towards Camden, he learned from the unit returns that instead of having 7,000 men as he believed, there were only just over 3,000 that were present and fit for duty. Hearing the news, Gates was unaffected; he believed that even with the smaller army, he outnumbered the British in Camden and had enough men to secure a victory.

Fact #5: The American diet before the battle hampered Gates’ army.

On July 27, 1780, General Horatio Gates ordered his new “Grand Army” south from Deep Creek, North Carolina towards Camden, South Carolina. Against the advice of many of his subordinates, Gates chose a direct route to Camden through barren countryside. The American army was already lacking food and supplies, but Gates was worried that if he did not move on this route of approach, he would fail to link up with the North Carolina militia that was assembled in northern South Carolina. Colonel Otho Holland Williams wrote that the route "was by nature barren, abounding with sandy plains, intersected by swamps, and very thinly inhabited." On August 15th, Gates ordered rations of meat, bread, and molasses for his men (molasses being a substitute for rum, of which Gates had little). Williams wrote later “The troops of general Gates’ army, had frequently felt the bad consequences of eating bad provisions; but, at this time, a hasty meal of quick baked bread and fresh beef, with a dessert of molasses, mixed with mush, or dumplings, operated so cathartically, as to disorder very many of the men, who were breaking the ranks all night, and were certainly much debilitated before the action commenced in the morning. From a mixture of bad bread, undercooked meat and the molasses, many of the Americans fell out sick on the night march towards Camden and others went into battle the next morning sick to their stomachs."

Fact #6: The British Army was very sick and undermanned.

While the condition of the American Army before the Battle of Camden is well-documented, the condition of the British Army is often overlooked. The outpost at Camden was not a healthy place in the summer of 1780. Lord Rawdon, commanding the forces at Camden, had a force of about 1,000 men, many of whom were unfit for duty. With the arrival of General Horatio Gates and his movement south from North Carolina, General Lord Cornwallis ordered other British outposts to send forces to Camden. Cornwallis himself arrived to take personal command on August 13th. Of the nearly 3,500 men on the rolls, only around 2,300 men were fit for duty on the evening of August 15th when the army began its march north. Cornwallis believed he could not defend Camden with the men he had. By moving to confront Gates he was hoping to catch him off guard and to give himself a chance to move the sick out of the town before the Americans arrived. Cornwallis knew he was outnumbered, but he hoped the element of surprise and his experienced troops would give him the upper hand.

Fact #7: The battle started with the armies accidentally running into each other.

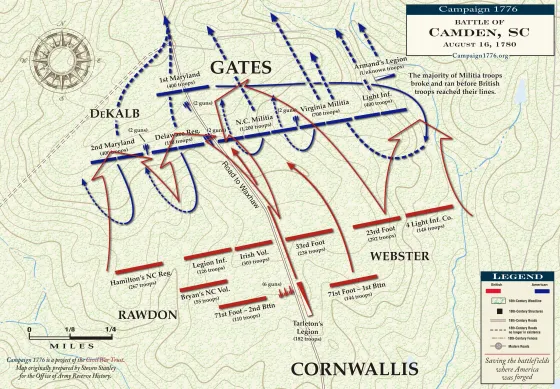

On August 15th, General Horatio Gates believed the time was right to move south from Rugeley’s Mill towards Camden. Gates was recently reinforced by several hundred Virginia militia and had two famed Carolina partisans, Thomas Sumter and Francis Marion, moving on the flank and rear of Camden. Gates ordered his men to move out at 10 pm, hoping a night march would protect his men from the heat and humidity of the Carolina summer and possibly steal a march on the British. Gates’ plan was not to attack Camden itself but to move to a defensible position north of Camden and force the British to either attack him or abandon Camden. The position he chose was the northern bank of Saunder’s Creek which was scouted out by his engineer, Lt. Col. Johann Christian Senf. Senf wrote, “reconnoitering a deep creek 7 miles in front was found impassable 7 miles to the right and about the same distance to the left, only at the place of the Ford interjects the great road.” General Lord Cornwallis was not inclined to wait for the Americans at Camden and moved northward near the same time that Gates moved south from Rugeley’s Mill. Cornwallis was an aggressive field commander and believed his best chance at victory was to prevent Gates from choosing the field or preparing his army. Additionally, Cornwallis knew he did not have enough men to fortify Camden. Colonel Otho Williams wrote later that “both armies, ignorant of each others' intentions, moved about the same hour of the same night, and approaching each other, met about halfway between their respective encampments at midnight. The first revelation of this new and unexpected scene was occasioned by a smart, mutual salutation of small arms between the advanced guards.”

Fact #8: Not all of the Americans ran from the field.

Though Camden is mostly known as a disaster for the Americans, a contingent of Continental troops fought hard and to the last. General Horatio Gates’ army was made up of predominantly untrained militia from Virginia and North Carolina. However, he also had the luxury of a small force of some of the best Continental troops in the entire American army, which were Continental soldiers from Maryland and Delaware that were under the command of Major General Johann de Kalb. Numbering only about 1,500, these men came from Washington’s northern army earlier that summer as a relief force for the Americans at Charleston. On the morning of August 16th, de Kalb’s Continentals were on the right flank of the American line. As the militia on the left broke, the Continentals held and even pushed ahead, forcing British troops back in their front. Soon, they were nearly surrounded, and there, de Kalb was mortally wounded (suffering from three gunshot wounds and several bayonet wounds). Eventually, the remaining Continentals made their way through the swamp thicket to the west. Only 50% of the Maryland and Delaware Continental forces made it out. Their bravery and hard fighting earned them the respect of many of the British officers.

Fact #9: General Gates’ famous ride from Camden

General Horatio Gates’ ride north after Camden was one of the most publicized events surrounding the Battle of Camden. As the American militia broke on the left, Gates was swept off the battlefield and personally retreated all the way to Charlotte that night (60 miles north) and then to Hillsborough, NC (120 miles from Camden) by August 19th. Gates’ critics, such as Alexander Hamilton quickly pounced on Gates’ behavior, “But was there ever an instance of a General running away as Gates has done from his whole army? And was there ever so precipitous a flight? One hundred and eighty miles in three days and a half. It does admirable credit to the activity of a man at his time of life.” Why didn’t Gates try to rally the men and why did he flee north as the Continentals under deKalb were making a stand? There is no clear answer, but one can imagine the chaos of battle and nearly 2,000 militia stampeding from a battlefield. Colonel Otho Holland Williams wrote a different view of the events, somewhat explaining Gates’ situation that morning. Williams wrote, “the torrent of unarmed militia, bore away with it, Generals Gates, Caswell, and a number of others, who soon saw that all was lost. General Gates, at first conceived a hope that he might rally at Clermont (Rugeley's Mill), a sufficient number to cover the retreat of the regulars; but, the farther they fled the more they were dispersed; and the generals soon found themselves abandoned by all but their aids.” It was not the plan or the battle that many believed cost Gates’ military career, it was the flight from the battlefield that caused his downfall. Some believe the harsh treatment of Gates was political, as Gates was an outspoken critic of Washington. Gates was not replaced as commander by General Nathanael Greene until December 3rd, nearly four months after his defeat at Camden. In that time, he did an admirable job rebuilding the army he saw nearly destroyed at Camden.

Fact #10: The Battle of Camden was the high tide for the British in the South.

The battle of August 16, 1780, was a military disaster for the Americans. General Horatio Gates lost nearly 2/3 of his army and the ensuing pursuit scattered his remaining forces. With his defeat, there were no organized Continental forces left in the south. The prospects for British success in the south would never be higher than mid-August in 1780. Soon, however, General Lord Cornwallis found out how hard it would be too “tame” the Carolinas. Constant fighting in the backcountry between Loyalists and Patriot militia (bolstered by partisans such as Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter, and Andrew Pickens) kept the British from reinstituting a Royal government. British frustrations guided strategic decisions that led to defeats at Kings Mountain and Cowpens a few months later.

Uncovering History

We invite you to visit the preserved locations along the Liberty Trail and to immerse

yourself in the extraordinary events that determined the fate of a nation.